A Call to Better Transit

VIA Metropolitan Transit is set to release free wireless internet on its entire fleet of buses next week, and they certainly want you to know about it. It is an accomplishment, indeed, to equip all 450 of its buses with wi-fi, though I’ve been told that service on an existing smartphone would probably still offer better surfing speeds than VIA’s service.

For all the splash that VIA is attempting to make with its wi-fi rollout, concerns linger about the basics that the transit agency seems yet to have perfected. In my own experience, for example, bus service has been lackluster at best. Throughout the last year, I have seen the system struggle with reliability, technical challenges, and poor driver etiquette.

Prior to moving to San Antonio I have used public transportation systems in Austin and College Station, Texas; Washington, DC; Rhode Island; and on visits to cities across the U.S., Europe, and Japan. The best systems, unsurprisingly, were in Europe and Japan, with the New York City and the Washington, DC services close behind. San Antonio, on the other hand, is wrought with issues that I believe can be fixed with careful planning and more effective management—not just the estimated $6 million* it cost to connect their buses to the web (*the estimate is based on the cost to equip San Diego’s bus fleet with wi-fi; VIA has not released the cost to have its service installed).

For most of my first year in town, I rode the route 94 bus, which offers express service from UTSA/The Rim to downtown San Antonio. VIA’s fleet of express buses are the most comfortable by far, and express service is exactly that: I averaged about 22 minutes from the University Park & Ride to City Hall and only a few minutes longer for the return trip, impressive for the 15-mile route. Unfortunately, there were many occasions when the 94 bus would run far behind schedule for arrival—even at 6:00 in the morning—and would often fail to show up altogether. I cannot even remember the number of times our group settled for a different bus route just to avoid waiting the extra 30 minutes for the next scheduled bus.

Since moving closer to downtown a month ago, the problems with bus reliability have ballooned. Nearly every bus I’ve taken has shown up after its scheduled time, with a northbound route 46 bus once showing up 25 minutes late (the bus only runs every half-hour). When I asked the driver if it was typical for the bus to run behind schedule, her excuse was unexpected: “I usually run late during the first week of the month because people are riding to pick up their checks.” Does this mean that whenever a bus has more passengers than usual, we can expect it to take 83 percent more time to reach our destination?

Because VIA’s bus schedules seem to be little more than suggestions, I have found that I rely heavily on its SMS/text service to find out how far away my bus actually is. It is fairly simple to use, requiring phone users to text a five-digit number to VIA in return for the arrival times of the next six scheduled buses. In theory, it is an effective service but, as I’ve learned, your mileage may vary. In many instances, the GPS unit installed on the bus is not functioning, resulting in no data coming through the text service. In other cases, the number of minutes shown until a bus arrives can be way off the mark—especially if the bus is moving through downtown. I’ve even had buses arrive at a stop minutes ahead of the reported time, causing me to miss it.

Perhaps the most preventable problem with VIA’s service lies with its drivers. While most drivers certainly do their jobs well, a few I’ve witnessed have a tendency to be rude, defensive, and inconsiderate. Once, after the 94 bus nearly left a dozen passengers waiting at the park-and-ride platform, the driver proceeded to argue with passengers about why they should have walked over to where she had stopped behind another bus—even though she stopped in an unpaved area beyond the platform. Last week I tried waving down a driver for not stopping, and because I was not close enough to the “flag” for her liking, she shook her head at me and kept driving. And just yesterday I witnessed who appeared to be a student from San Antonio College run at full speed to catch the route 3 (a skip-service bus), just to have it drive off as she reached the front door.

Aside from problems with reliability, technology, and lack of driver sympathy, VIA’s system also suffers from other issues that need to be addressed. Its bus pairing, for instance, is incredibly complicated from a user standpoint. There is no apparent logic to why a bus would have the number 2 north of downtown, but continue as route 34 south of downtown, or why routes 36 and 90 are the same bus. Similarly, if a frequent route is paired with a less-frequent route (as is the case with routes 3 and 46), southbound passengers are dumped downtown to wait for another bus, making travel planning even more challenging. Worse, drivers sometimes change their digital displays at the wrong location, leaving passengers who are waiting for the route 4 wondering why a route 20 bus has shown up instead.

Another challenge to be addressed is the location of bus stops. I have heard transit folks debate the merits of near-side stops versus far-side stops (for the uninitiated, it simply refers to whether a bus stop is located before an intersection or after one). Usually the arguments have to do with traffic flow optimization, which I personally believe is a terrible way to decide where transit users should become pedestrians. A prime example of this failure occurs at the intersection of Pleasanton Road and SW Military Highway on San Antonio’s south side. VIA is planning to turn SW Military into one of its next PRIMO routes, a less-than-BRT system, and has at one point considered placing its new westbound stop at the northwest corner of the intersection. Considering that the primary destination at this intersection, an H-E-B grocery store, is at the northeast corner, a far-side stop placement seems completely ridiculous (see photo). Why should a bus rider that is carrying groceries be expected to cross a dangerous intersection to catch an “enhanced” bus, all in the name of right-turning vehicles who would likely be in conflict with those very same grocery-hauling pedestrians anyway?

The intersection of San Pedro and Hildebrand avenues, a couple miles north of downtown, is also problematic from a transit user point-of-view. It is a fairly compact intersection, with four lanes heading east-west along Hildebrand and four lanes with a center turn lane running north-south along San Pedro. For passengers like me who get off the bus at the northeast corner of the intersection but want to get to the southwest corner, traversing this intersection has taken more than 3 minutes—an eternity when traffic whizzes by at 40 miles per hour in 100-degree heat. Partly to blame, here, is that traffic in each direction on Hildebrand gets its own signal due to the fact it has no dedicated turn lane. Shortening the cycle times for all traffic would certainly help pedestrians, although a dedicated pedestrian cycle would be ideal, considering more than 400 people get on and off the buses that serve this intersection daily.

The two intersections I’ve mentioned so far actually feature sidewalks, but countless other bus stops seemingly dump passengers onto very precarious locations. One troublesome stop is one I experienced yesterday evening in Alamo Heights just west of the intersection of Austin Highway and N New Braunfels Avenue (see photo). This section of Austin Highway not only lacks sidewalks, but heading northeast on Austin Highway I found that a guard rail actually prevented me from getting to the intersection, forcing me to either walk in traffic or jaywalk to the other side of Austin Highway. Not an ideal situation, to say the least.

I could continue down the list of problems VIA needs to fix but, in reality, the first thing that any transit agency needs is to require its leadership to actually use the bus system. A CEO that gets into his car to go to work each day can’t possibly understand the trials of someone who commutes via transit each day. Jeffrey Arndt may occasionally worry whether his car will start in the morning, but he probably won’t face a biting dog on the way to his garage, nor will he have to stand next to a freight train in the heat or get splashed by cars driving through puddles. Likewise, a Board of Trustees who does not use its own system cannot empathize with a concerned public when their role is to defend VIA at all costs.

In 2011, Houston Metro’s president and CEO changed its policy, requiring senior managers to ride public transit 40 times per month. And I think that Metro’s George Greanias said it best: “I know of no business where you can be successful without using your own product and believing in it.”

So this is a call to Jeffrey Arndt, Keith Hom, Hope Andrade, Steve Allison, and the rest of VIA Metropolitan Transit’s Board and Executive Leadership Team. Do you believe enough in your product to use it and improve it?

22 contradictions that show we can’t be trusted to make good decisions for our cities

So often I’m struck by the ways our positions on neighborhoods and cities contradict each other. We say we’re for affordable housing, but oppose any affordable housing near us. We say we want to live a green lifestyle, but refuse to give up our big backyards. Anyway, here’s a fun (or perhaps frustrating) list of 22 contradictions that show we can’t be trusted to make good decisions about the places we live:

- Toll roads are unfair, but transit should pay for itself.

- There has been no investment in my neighborhood for years, but gentrification is evil.

- Housing is getting so expensive here; therefore, let’s not build any more.

- Traffic is terrible, so I bought a house that requires me to own a car.

- Developers are the scum of the earth; apparently, my house wasn’t built by one of them.

- America is a democracy, so these five property owners will decide the fate of my neighborhood.

- I played outside unsupervised all day as a child, but my kid will surely be kidnapped if left alone for five minutes; the fact that crime rates have fallen dramatically since I was young is irrelevant.

- I moved downtown to be close to all the action but, man, are these live music venues loud or what!

- Surely the 35 granny flats that get built next year will ruin our city, but those 350 new homes outside the loop? Meh.

- It’s too unsafe for my child to walk to school because of all the cars, so I drive him.

- It costs $6.00 to park in this lot two blocks away, but this really convenient meter in front of the restaurant is only $1.00 an hour.

- People aren’t riding the bus because it only comes once an hour, so they had to cut service.

- Walmart is an evil corporation, but—hey, look—there’s a Target going in over there.

- I want to live in a walkable neighborhood, but I don’t want to be too close to anything that’s not a house.

- This new freeway interchange will cost taxpayers $400 million…oh, that’s cool. The city is considering dedicating $75 million to a new transit line…SOCIALISM!

- I demand lower property taxes! By the way, why haven’t those road crews come to fix this pothole?

- Population density is really high in that neighborhood, so it’s too complicated to install rail there.

- I spent thousands of dollars to travel to Europe to enjoy their beautiful cities, but this is America…we’re different.

- Traffic deaths are terrible…Let’s be a Vision Zero city! Sweet, they just raised the speed limit on this road to 75!

- I will spend five minutes looking for a decent parking spot to spend 30 minutes on a treadmill.

- I demand to be able to vote ‘no’ on transit projects. Roads, sewer service, sidewalks, electricity, cable, free parking…now those are my rights.

- Living near the university gives us access to so many great restaurants and venues, but college kids are just the worst!

Can you think of any that I missed?

A Youthful Perspective on the Built Environment (Guest Post)

A good friend of mine, David Clear, had the rare opportunity today to speak with local youth about public health and our built environment. He agreed to let me adapt his email to share with you all the amazing insight these teenagers gave:

Today I had the honor of speaking at the Public Health Camp put on by the University of Texas Health Science Center’s School of Public Health. I had a great day interacting with the youth of our San Antonio high schools, particularly those interested in health careers.

One of the questions I posed after our discussion was how many of the youth planned to leave San Antonio and not come back. The answer was over 50%. When I asked the reasons for this, I was pretty shocked by the overall answer: the built environment sucks. When I asked whether they were interested in cars, the overwhelming answer was no. They mentioned they grew up in the back seat of cars, being shuttled from appointment to appointment or, more often, stuck in traffic. Another reason cited for not wanting to drive was how expensive it is. What they are interested in paralleled what national research suggests about our youth: they want safe streets and hip, vibrant communities with places they can get to without a car or dealing with car congestion.

Then I asked, if San Antonio was to do anything to ensure that they would stay in San Antonio after their college years, what would it be? Their responses are broken down below:

- Prioritize the city’s budget to reflect quality of life investments such as safe streets and parks

- Change legislation to require minimum guidelines for safe streets

- Correct unsafe corners, particularly for bicyclists by improving intersection design

- Deal more effectively with pedestrian and bicycle barriers such as power poles, overgrown shrubs, etc., particularly at intersections

- Start to focus downtown and then expand from there

- Improve bike and transit infrastructure

Overall, these youth expressed that they just want to stay involved in the process.

So, what would be your strategy for getting teenagers and youth better involved in the planning and policy development of our cities? I’d love to read your comments, and I’ll be sure to pass them along to David.

Addressing Gentrification in San Antonio

Since moving to San Antonio more than eight months ago, I have watched the local debate on gentrification take on a life of its own. I’ve read articles chronicling our changing neighborhoods, I’ve watched town hall meetings get completely derailed by distractions, and I’ve observed nearly all the meetings of the Mayor’s Task Force on Preserving Dynamic and Diverse Neighborhoods. The passion demonstrated by many of the folks who attend, write about, and speak at these meetings is admirable; yet, I can’t help but believe that they’re also a bit off base. Here are my three main points:

- The degree to which gentrification is actually happening in San Antonio has been wildly overblown.

The impetus for this local debate seems to stem from a shuttered mobile home park that was rezoned about a year ago. Its zoning was changed so that developer White-Conlee could buy and redevelop the site with about 400 apartments. Regardless of what those apartments eventually look like, writers have characterized the redevelopment as “high-priced,” “high-end,” or “luxury,” in a pejorative sense as a way of contrasting it against the mobile homes that had been on the property until early this year.

To be clear, I can sympathize with the residents of Mission Trails. I know what it’s like to face housing instability and to be displaced from my home. I’ve been pushed to seek new housing—twice—with just 30 days notice. On one of those two occasions I had to sleep on an acquaintance’s couch for weeks before I could move into my new place. On the other, I moved in with my best friend and his new bride for several months, living out of boxes until my move to Texas. Not having a place to call ‘home’ is stressful.

But I have seen the victimization of Mission Trails residents taken much too far in the media and at public meetings. Several of the facts have been left out of the conversation, allowing generations of mistrust to boil over within the public forum.

Fact: Mission Trails residents rented the spaces where their homes were sited; this, by nature, is a temporary arrangement. Despite some of the residents living there for decades, the owner/landlord had no legal obligation to keep the property as a mobile home park.

Fact: This was not the first time Mission Trails Mobile Home Park had been offered for sale. To pretend that the sale of the property was sudden and unforeseen, or that it was caused by improvements to the river, is just plain wrong.

Fact: Conditions at Mission Trails were deplorable for years. And, because streets within the community were privately owned and maintained, the City was not responsible for street repairs, trash pickup, and so on. A search in Google Street View shows the poor condition of the property as far back as 2007. This is in contrast to Mark Reagan’s account of Mission Trails in the San Antonio Current, which implied that “water-filled potholes” and “dilapidated trails” were a result of the City’s neglect after rezoning the property.

Fact: The reason cities continue to de-emphasize mobile homes is because they were never built to be permanent housing. Like any other automobile, mobile homes lose value rapidly over time, and issuing protections for mobile homes is not an investment that taxpayers should be supporting. That being said, policies that allow mobile home owners to acquire land as well as replace their homes with low-cost, permanent structures are asset-building strategies worth pursuing further.

Fact: The developer did not seek government incentives for the purchase of the property; thus, White-Conlee had no legal obligation to compensate the families at Mission Trails. In fact, the dollar value of relocation assistance to residents was reported to be upwards of $7,500 per household, likely more than they would have received through the Uniform Relocation Act (which only applies to federally-funded projects). Yet, several families continued to cry to the media that their rights were being taken away.

Another local story that has seen its share of press is the issuing of a demolition order for Miguel Calzada’s home in the Beacon Hill neighborhood. Legend now has it that an investor harassed the elderly homeowner about purchasing his home but, after refusing to sell, the angry investor turned the man in to code enforcement, resulting in an order to demolish the dilapidated home in order to force the sale of the property. Several folks, like former councilwoman Maria Berriozábal, have turned this story into the face of gentrification. And Page Graham of The Rivard Report bought into it, painting the portrait of yet another victim of gentrification:

“The City was apparently intent upon tearing down the house and sending him the bill for the demolition…As a humble homeowner who runs a salvage business for a living, standing in front of a dais filled with people he perceived to be unsympathetic to his plight was intimidating to say the least…”

Then, just two days later a follow-up article appeared with a hashtag: #SaveMiguelsHome. It detailed the work of several politicians and community activists showing up on a Saturday to clear out the Calzada’s home in an attempt to stave off demolition. But, as one commenter pointed out, the sudden outpouring of support seemed perfectly timed with the start of campaign season. I think the issue of the proposed demolition was best summed up in the following comment:

“…[T]he Calzadas are NOT the ‘face of gentrification.’ They are a victim of unfortunate circumstances and mounting home maintenance costs, but they are not victims of gentrification. Again, I support communities coming together to “love thy neighbor,” but let’s not confuse one with the other. Furthermore, calling Beacon Hill a ‘hotbed’ for house flippers and developers is an overstatement at best. In fact, we do a disservice to our neighborhoods when we use language like this because it proposes that reinvestment is a zero-sum game…either we’re gentrifying a neighborhood or we’re letting it rot–there seems to be no welcome in between. Then, when someone comes in and builds one house or a fourplex, suddenly the existing residents are at risk? Really?”

The unfortunate reality of Mission Trails and the proposed demolition of Calzada’s Beacon Hill home are not stories of gentrification, but of limited resources for families in situational and generational poverty. It is true that throughout our city we have thousands of families living in homes they can’t afford to maintain and improve. But, part of this conversation needs to include the question, “whose responsibility is it?” When an owner’s home falls into disrepair, is it fair to blame others for their plight?

- The misrepresentation of developers, politicians, city staffers, and “the gentrifiers” continues to undermine the credibility of those advocating for policy changes

From sea to shining sea, stories of gentrification continue to paint a very antagonistic picture of neighborhood change. Developers are portrayed as greedy, politicians corrupt and holding hands with those greedy developers, city staffers are seen as looking for ways to swindle their fellow man, and wealthy white citizens couldn’t care less about how their desire to move downtown affects the poor. Frankly, these are lazy generalizations that are just as insidious as stereotypes about lower-income families and minorities. The truth is that we need developers who risk investing in forgotten neighborhoods just as much as we need protections for residents who’ve lived in these neighborhoods for decades. We need politicians who will balance the needs of the poor with those of the middle-class while, at the same time, crowding out baseless accusations of collusion. We need city workers to help provide the research and data to help guide the decision-making of our mayors and council members. And, yes, we even need the so-called gentrifiers—the ones who bring additional capital into existing neighborhoods—both financial capital and human capital—to restore vacant, neglected homes and fill empty retail spaces with thriving new businesses.

Here in San Antonio, not unlike many other cities, we have advocacy groups that thwart progress simply by generating dissent among fellow citizens. I watched this unfold time and again at town hall meetings for the Mayor’s Task Force on Preserving Dynamic and Diverse Neighborhoods. Both the Texas Organizing Project and Esperanza Peace and Justice Center have shown up in force at these meetings over the last month, creating obvious distractions from the point of the meetings, which was to actually debate the content of the Task Force’s report. Instead, we had folks creating a spectacle out of the fact that translation services weren’t provided. Sadly, it set a very unproductive tone for the rest of the meetings where it was no longer about discussing and revising content, but about controlling the damage brought on by the very people the report is intended to help. What’s worse is that none of these so-called advocates have yet to offer any real, data-driven guidance on how to balance progress and protection. On the contrary, they have had a notorious history of causing controversy, as was the case during the December ribbon cutting ceremony of the Alamo Beer Company.

Even some of the Task Force members have contributed to the dissent. Both Maria Berriozábal and Nettie Hinton, each long-time neighborhood advocates, never hesitated to deflect blame onto the City whenever the collective work of the group didn’t reflect their personal stances on gentrification. They each continued to insist that the report was staff-driven, even though anyone who has watched the Task Force in action knows that the recommendations came straight from their (sometimes unfocused) conversations. Ms. Hinton, in particular, vilified Cherry Street Modern on several occasions as a high-end apartment complex (it is neither high-end nor an apartment complex), and plainly called the small development “ugly.” She is certainly entitled to that opinion, but it seems hardly fair to call modest, two-story modernist homes ugly when compared to the numerous industrial buildings that still exist just across the street. In fact, here’s the current view from the small, 12-unit development:

- Income segregation and suburban sprawl are generally ignored by those opposing anything resembling gentrification

A report that’s been floating around at recent meetings is one from the Pew Research Institute which shows San Antonio as the most income-segregated metro area in the nation. This means that, more than anywhere else in America, lower-income San Antonians live near other low-income San Antonians while those with higher incomes tend to live near others with higher incomes. Although evidence of the benefits of mixed-income communities is still nascent, the data on the ill effects of concentrated poverty are much more robust. According to the Brookings Institute, “concentration of poverty results in higher crime rates, underperforming public schools, poor housing and health conditions, as well as limited access to private services and job opportunities.”

Thankfully our current mayor, Ivy Taylor, understands this reality. In fact, at a recent meeting of the Mayor’s Task Force on Preserving Dynamic and Diverse neighborhoods, she stood up to one task force member who suggested that all new housing on San Antonio’s East Side be affordable to the low-income residents who have lived there for generations. “I reject the notion that the East Side should remain a predominantly low-income neighborhood,” Taylor said, passionately.

As I alluded to in a previous post, one of our great failures in the urban planning community is supporting policies that allowed suburban sprawl to supplant a focus on inner city development for decades, leaving our urban cores to deteriorate throughout the latter half of the 20th Century. More than 60 years after the advent of modern suburbia, we continue to let a history of ‘white flight’ inform our development decisions, resulting in some of the most inequitable neighborhoods in our history. Looking at that same Pew Research Institute study, the majority of our most income-segregated cities are those that grew up around an auto-oriented, suburban planning regime: Houston, Dallas, Denver, Los Angeles, and Phoenix.

Today, many cities, including San Antonio, are beginning to fill in with urban projects that opponents of gentrification love to hate. This includes the wholesale redevelopment of the former Pearl brewery, now home to over 600 newly-built apartments, boutique retail shops, local restaurants, a weekly farmer’s market, and a campus for the Culinary Institute of America. It includes the renaissance of Southtown, including the now-hip Lavaca and King William neighborhoods. It includes the Hays Street Bridge redevelopment and Alamo Brewery in burgeoning Dignowity Hill. These are all places that are anecdotally known as agents of gentrification—that is, places catering only to the wealthiest and whitest people. Except that, in San Antonio at least, it’s untrue.

Using methodology similar to that in Pew’s Residential Income Segregation Index, none of the San Antonio neighborhoods mentioned live up to their gentrified reputations. The area around the Pearl is majority middle-income; that is, most households there earn between $30,000 and $100,000 per year. The same is true for the King William district, Lavaca, and portions of Beacon Hill. Other supposed centers of gentrification in San Antonio, like Lone Star, Tobin Hill, and Dignowity Hill, remain majority low-income neighborhoods. These are areas where the majority of households earn less than $30,000 per year. Economist Joe Cortright takes it a step further in his research, showing that places that were mostly poor in 1970 are still that way today and, in fact, there are more areas of concentrated poverty in American cities than there were 40 years ago.

—–

It is frustrating to watch elected officials dedicate precious civic time on policies for a problem that isn’t nearly the problem advocates would have us believe. I am all for being proactive, but the rhetoric being spread by outlets like the San Antonio Current, The Rivard Report, the San Antonio Express-News, Univision 41, and by groups like TOP and Esperanza is anything but proactive. Especially concerning to me is that groups like Esperanza are actively writing the public narrative on gentrification: on April 18th the organization held a forum called, “Gentrification and the Right to Remain,” bringing four mayoral candidates to speak on the subject. Naturally, the focus of the questions was on projects that Esperanza publicly opposed, opening a door only for the candidates to say what audience members wanted to hear.

To me, both the local and national debate on gentrification boils down to one thing: people use five percent of the facts to make up 100 percent of their mind. And that kind of ignorance, my friends, is not bliss.

Walking on SoFlo: A Photo Journal

Outside of San Antonio’s immediate downtown, few corridors have the potential to be a great street the way South Flores does. For those unfamiliar, SoFlo is a 4-laner that runs north-south, sitting halfway between Interstate 10/35 and the San Antonio River.

Today, South Flores is a hodgepodge of buildings and uses, and its pedestrian environment is just as varied. Along the 1-mile walk between my office and the VIA Express bus stop downtown, there’s a collection of loft apartment buildings, light industry, law offices, a child care center, a Crossfit gym, a parking garage for the County Courthouse, several surface parking lots, and numerous vacant properties. It is also home to the HEB headquarters, where there will soon be the city’s first true downtown grocery store in a long time (Hooray!).

Geography of the Generational Divide

I believe it has been pretty well documented, up to this point, the negative effects of both racial and income segregation in our cities. And, of course, those negative effects tend to be magnified when majority middle- and upper-income white neighborhoods are starkly divided from lower-income minority neighborhoods. But what about neighborhoods that are divided on the basis of age?

As I was looking through some data here in San Antonio, I realized that not only are we segregated on the basis of race and income—in fact, we hold the distinction of being the most income segregated large city in the nation—we’re also pretty segregated by generation.

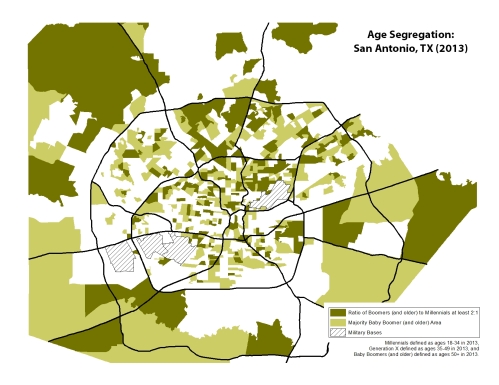

Take a look at this first map above. Areas in the light green are those whose majority population are Baby Boomers or older (ages 50 and above, as of 2013). Areas in the darker green are those whose 50-plus population outnumbers Millennials (ages 18 to 34) by a ratio of 2 to 1. This greater share of Boomers and older adults is concentrated in wealthier suburban enclaves, such as Shavano Park, Castle Hills, Olmos Park, Terrell Hills, Alamo Heights, and Cross Mountain/Dominion. They also hold a majority in urban neighborhoods including downtown, Tobin Hill, and Southtown/King William. Interestingly, most of the region’s highest-ranked corridors in the state for traffic congestion are in majority Boomer areas—I-35 between Fort Sam Houston and Loop 1604, Loop 410 between I-10 and US-281, US-281 in the Stone Oak area, and Bandera Road on the Far West side.

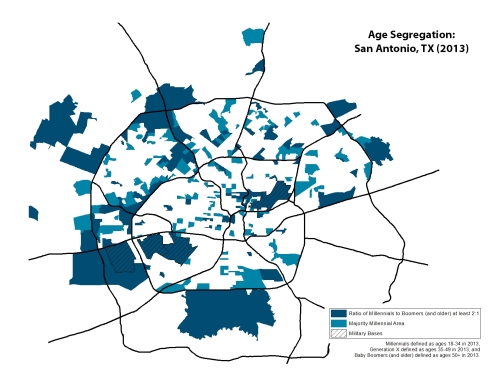

This next map shows San Antonio’s younger adult population, with areas in the lighter blue indicating a majority Millennial population. Areas in the darker blue show where Millennials outnumber the 50-plus group by 2-to-1. Not surprisingly, some of the largest gatherings of Millennials can be found on our military bases and around college campuses. Other Millennial locales include the Pearl Brewery/Museum Reach area, Mahncke Park, Medical Center, Brooks City-Base, and the Westover Hills area. Another important note is that most majority Millennial areas are found inside Loop 1604, whereas Baby Boomers and older adults are found in greater shares in the periphery. This tends to jive with data that indicates a preference for younger adults to live closer to the city center.

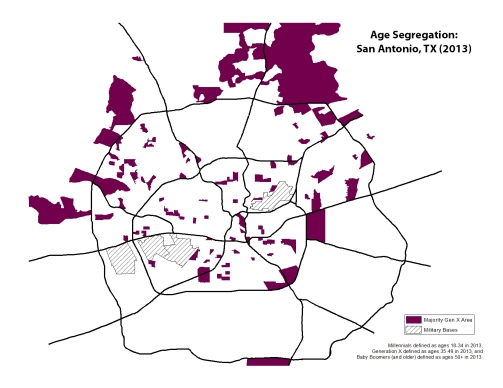

Generation X, consisting of adults between the ages of 35 and 49, don’t make up a huge chunk of San Antonio’s population overall. But, it is interesting to see in the map above where Gen X-ers predominate. The late-30s and 40-somethings are most concentrated on the Far West side and in the Far North Central area most referred to as Stone Oak. A good portion of these majority-X areas fall outside the city limits for San Antonio.

What do we make of all of this?

It seems that we’re at a bit of a crossroads in terms of neighborhood preferences and realities. Those in the 35-to-65 age bracket have been moving increasingly outward into the periphery, bringing with them a blend of circumstances that are only growing the gap between the haves and the have-nots. Younger adults are arriving into previously disinvested neighborhoods, saddled with debt and fueling its own brand of resentment among long-time residents. In between them are the oldest adults, stuck with the original suburbia: homes that, 60 years later, lack the high-end finishes and square footage expected by the Gen X-ers or the conveniences and quality schools expected by Millennials.

There are social consequences to age segregation as well. Lack of interaction between older and younger adults tends to breed distrust toward the other, allowing media outlets to reinforce negative stereotypes about each other’s generations. Children also lose out when they only socialize with other kids, as they fail to develop the skills necessary to navigate a world run by adults, or gain hands-on skills that are quickly disappearing from our workforce. In turn, adults treat children as fully-dependent, untrustworthy beings, incapable of playing outside or using public transit without constant supervision.

While not a silver bullet, adapting our built environment is a key piece to our ending segregation (in all its forms). In some cases, it will require developers to make wholesale purchases of deteriorating homes and modernizing them to meet the needs of today’s households. It requires easing zoning and lending restrictions on densifying our existing neighborhoods—allowing residents to build a small, second home on their property or converting existing houses to better accommodate nontraditional households (e.g. roommates). It requires thoughtful innovation about how transit can be more effective at getting residents around our city. It requires standing up to the ‘I-was-here-first’ cries of homeowners in central neighborhoods who believe their property rights extend beyond their fence. It requires honest evaluation of how we meet the housing needs of a changing American demographic—one that is fast rendering the typical suburban subdivision obsolete. It especially requires that we look at how we have gerrymandered school boundaries to keep poor kids out of wealthier schools.

An Honest Look at Gentrification & Sprawl

(edited on 12/4, 10:00am)

The term gentrification has been thrown around for decades. A quick search will reveal seemingly countless articles and blog posts on the subject. Yet, even now it seems few people agree on what gentrification actually is. In the public realm some see gentrification as a process by which lower-income minorities are pushed out of an urban neighborhood; others see it merely as positive reinvestment in a formerly “forgotten” part of town.

I, too, struggle with defining this phenomenon. Does gentrification automatically lead to displacement of long-time residents? If reinvestment in an area can be done while avoiding rapid displacement, does it still count as gentrification? And, is it still gentrification when middle-income households are the existing residents seemingly priced out of a neighborhood by those of an even-higher income bracket?

While researchers continue to study and debate the manifestations of gentrification, I believe a more expedient question is whether gentrification is more or less preferable to sprawling development. In other words, whose impact is more positive or negative: gentrification or suburban sprawl?

If we take the basic assumptions about gentrification as factual, then evidence of gentrification would include construction of new housing—whether single-family or multifamily; “filtering up” of existing housing to wealthier residents; demolition of blighted or so-called “obsolete” properties; changes in commercial tenants to those catering to middle- and upper-income consumers; and, sometimes, improvements in public school performance measures. Side effects of this phenomenon can include increases in property taxes, spikes in rent, reduction in crime, loss of cultural or racial diversity, greater architectural variety, increased investment in local schools, and potential loss of cultural or historic assets.

On the other end of the spectrum, suburban sprawl is evidenced by new development on greenfield sites—that is, land that was previously in its natural or agricultural state; housing that is segregated by even small differences in value; land uses that are purposely disconnected from one another; larger and newer buildings; and, wider streets with higher speed traffic. Side effects of sprawl can include increased vehicle miles traveled, increased per capita emissions, lower per-square-foot costs of land and housing, loss of arable land, impervious surfaces that lead to greater flash flooding, inequities between suburban and urban schools, disinvestment in inner-city neighborhoods, increased maintenance costs for extended infrastructure, higher city expenditures to cover required public safety needs, and a reduction in accessibility for transit users, bicyclists and pedestrians.

My point is this: how can we advocate against both suburban sprawl and gentrification without thinking realistically about the implications of either phenomenon? Yet, this is precisely what we are seeing from politicians and advocacy groups all around us. We have mayoral candidates in Austin claiming that salvaging housing affordability and relieving traffic congestion are crucial, but in the same breath suggesting that inner-city neighborhoods should be allowed to opt out of the types of development that allow for anticipated growth—even when those development types serve to protect historic resources. I’ve mentioned here before the audacity of residents to publicly oppose regulations that allow more accessory dwelling units (a.k.a. granny flats or garage apartments) to be built in existing neighborhoods, even when they benefit financially from such units themselves. Unfortunately these biases are not unique to Austin.

In Hartford, Connecticut, some are now questioning what constitutes a family after a group of eight adults and three children living under one roof were hit with a cease-and-desist order when neighbors complained—despite their home’s nine bedrooms in 6,000 square feet, and even a concession by neighbors that the residents “are nice people,”—all because they don’t fit the definition of family outlined in the city’s zoning ordinance.

When it comes to discussions of gentrification, or sprawl for that matter, fostering or advocating for neighborhood exclusivity is antithetical to the broader goals of affordability and sustainability held by many communities.

For starters, using gross hyperbole to sell one’s view of either gentrification or sprawl gets us nowhere. And nowhere is this more evident than in an article that came into my work inbox this week entitled, “How Oligarchs Destroyed a Major American City.” In this diatribe by Anis Shivani, he laments the changes in his long-affluent Montrose neighborhood of Houston, calling it “…the most monstrous example of gentrification…” Sadly, that is just the start. I began highlighting all the colorful language throughout his op-ed piece, and here are but a handful of those highlights:

“Houston has transmogrified into a city ruled by a brutal strain of neoliberalism…”

“…the city is being hollowed out…”

“…victims of the grotesque leveraging of urban space…”

“…gangsters dressed in nice suits.”

“…displaced by unoccupied zombie high-rises…”

“…gratuitous violence against helpless tenants.”

This all sounds like it came from a novel, don’t you think? Then it occurred to me while reading this piece that Shivani is primarily a fiction writer, and it seems he has used his literary prowess to paint an imaginary portrait of gentrification where the evil, money-hungry monster developer is colluding with corrupt politicians to bulldoze idyllic utopian neighborhoods and replace them with a treeless landscape of windowless castles for the one percent of the one percent.

Another fiction writer, Vann Newkirk II, also used quite the paintbrush to describe gentrification in one Washington, DC neighborhood:

“The Safeway…was a disaster. Rotten meat regularly rested on refrigerated shelves and the stench spilled into the parking lot…This was the story for years until 2012, when the building was demolished to make way for the construction of a new incarnation of the store,” he began. “The new sprawling citadel of a Safeway returned triumphantly in 2014 to a coffee-scented community of swanky condo blocks, cyclists and more young white faces than ever.”

He goes on to make an interesting conclusion:

“Perhaps, then, it’s adequate to look at grocery stores more as agents of gentrification and potential weapons of cultural violence against the poor than as saviors for our country’s obesity epidemic.”

And here I thought grocery stores just sold food.

In all seriousness, there are real beings living with the negative consequences of both gentrification and sprawl. But, we cannot vilify both without offering real solutions, because today there appears to be little alternative without intervention.

So what does that intervention look like?

First and foremost, we must learn to identify where gentrification is happening and where it is not. Anecdotal stories of pawn-shop-turned-café and eviction notices will not suffice. This requires a close examination of changes in property values relative to other neighborhoods in a city, changes in rents over time, changes in both numbers and percentages of racial/ethnic groups, data on school enrollment and test scores, changes in both numbers and percentages of housing types, changes in availability of subsidized housing, and a breakdown of housing availability by price point.

If this data indicates that people are truly being displaced, another important step is to determine the fate of those residents. Were they involuntarily displaced or did they leave on their own accord? Were they compensated fairly for their property and/or for relocation costs? Where did they move? Are they satisfied with their current living arrangements?

News reporters and fiction writers know that coverage of the elderly woman sobbing at the thought of being ripped from her longtime residence is what tugs at our heart strings. We have made that the face of gentrification. But rarely, if ever, do we learn that developers often provide even more relocation assistance than is required by law or even what many employers might cover for relocating one of its own employees to another city. We fail to catch a glimpse of the hopeless conditions in which many of these people being relocated were facing each day. We also fail to ask later if the ones who relocated have improved their quality of life as a result.

I want to be clear: I am not advocating displacement as an appropriate first measure to revitalization in most instances. We must work, instead, to break the inequities our current system can cause. I simply mean to caution against jumping to the conclusion that developers and city leaders are driving street-by-street with demolition orders in hand. That is rarely ever true.

Next, we must learn to identify future stages of gentrification, whether in currently gentrifying neighborhoods or in neighborhoods most at-risk. Is the trajectory of housing prices still heading upward at a rapid pace, or has the growth slowed? Are there plans in place for some catalytic project, like a technology campus or rapid transit line that could boost the desirability of an area? Is there a strong inventory of architecturally significant housing in need of restoration? Are local businesses beginning to see a loss in clientele due to their relocation?

Then, we can begin to identify development types and policies that will have the most positive outcome for both new and existing neighborhood residents. Some researchers recommend infill housing as a first defense to the negative effects of gentrification; that is, building new housing on vacant parcels and in place of undesirable properties such as abandoned warehouses. Acquiring these properties while values are still relatively low can help provide this early housing at a reasonable price that meets the initial demand in a neighborhood while other policies are put in place to protect long-time residents.

Such policies for existing residents may include offering housing rehabilitation assistance to homeowners that help bring their homes up to code; offering rehab assistance to both residential and commercial landlords in exchange for limiting rent increases to tenants; targeting housing vouchers to gentrifying areas to allow existing residents to meet mounting expenses; offering counseling to residents who may want to sell their homes; initiating property tax freezes for residents who have occupied their homes for a specified time period; mandating relocation assistance for residents being displaced from unsubsidized developments; and, considering legislation that caps rent increases in the same manner that many states cap property tax increases.

As housing stock does begin to turn over, it is also imperative that these urban neighborhoods foster increased density to accommodate the population growth of our cities. While people often assume this means adding high-rises to single-family neighborhoods, this is generally not the case—nor is it legal in most places. Rather, many development types that have largely disappeared from the housing landscape since World War II are those in-between solutions that fit well into the context of an existing neighborhood. Appropriately called “missing middle” housing because they fall between single-family homes and traditional apartment complexes, these include well-known examples like duplexes and townhouses, but also less common models like micro units, accessory dwelling units (as I mentioned earlier), bungalow courts, small condominium buildings, small lot subdivisions, and live-work units. What is especially promising about these missing middle developments is that some can offer direct protection for long-time neighborhood residents by allowing them the opportunity to earn rental income to offset their growing housing costs. Even a nonprofit could help finance the construction of accessory dwelling units on the properties of lower-income homeowners, allowing them to generate that needed income in exchange for a manageable monthly fee and partial lien on the home, as one friend had considered pursuing. Some jurisdictions may consider requiring that those ADUs be kept available as affordable housing.

Some broader obstacles still exist that prevent missing middle housing from being built in many cities. Often, lenders prefer to offer credit for the most proven development types—namely, single-family housing and single-use commercial development. Working with lenders and finance policymakers to increase the availability of funds for less conventional housing types will be critical. Also, many centrally located parcels are designated with zoning that keeps these more affordable housing types from being built. Upzoning some these parcels to allow for more flexible development is one way to move these forward. Similarly, high minimum parking requirements often artificially limit the number of units that can be built on a parcel. Relaxing these minimums in walkable and transit-rich areas can help to increase the availability of affordable housing in areas that may be starting to see some of the pressures of gentrification.

Finally, we must counter the resistance to development types that are unfamiliar or may at first appear to have an undesirable impact on a neighborhood. We tend to associate these housing types with past memories, and more often than not, those memories are negative. Duplexes, for example, tend to be associated with concentrated poverty. Micro units tend to be associated with overcrowding. However, neither of these associations is actually true. Working with residents to break these stereotypes and ensure they understand how these missing middle housing types will result in a net benefit to the neighborhood is imperative to their adoption.

At the end of the day, it remains a challenge to define gentrification in a definitive way. But we all claim to know it when we see it. Rather than continue to beat the proverbial dead horse over semantics, we need to work together to remove the obstacles to revitalizing our centrally-located neighborhoods while also protecting the people and assets that make these communities attractive in the first place. This means gathering data that may seem difficult to obtain, advocating for equitable policies that may not always suit a city’s wealthiest or most powerful constituents, and breaking down the barriers to development types that represent a growing number of our citizens’ American Dream. It even means challenging the vocal few who refuse to dialogue honestly about the collective needs of the community (rather than just their individual desires) and instead reject change altogether simply because it is uncomfortable.

Where does this leave suburban sprawl? My personal perceptions of suburbia aside, it is not until we remove the hurdles to inner city redevelopment and restore equilibrium to the burden caused by greenfield development that we can slow the unnecessarily damaging expansion happening at our peripheries. What does that mean exactly? It means restoring balance to the costs of development—that is, ensuring households living farther from the core pay their share proportionally necessary to offset both the visible and invisible weight we place on our infrastructure, including the additional miles of roadway to serve these areas; the added length of sewer lines, water lines, and power lines; the potential flooding impacts associated with increased paving; the loss of valuable wildlife habitat; the extension of transit service into the broader commuter shed; the stress on our water supply caused by excessive landscape irrigation; the stress on our power grid caused by heating and cooling our ever-larger homes and commercial buildings; and, the costs needed to construct and operate public facilities in order to keep emergency response times low as well as maintain desirable recreational amenities.

Whether our preference is for an urban lifestyle or a more suburban one, we can no longer accept the premise that either is without its costs. The truth is that our current system—complex as it may be—creates winners and losers in both circumstances. Gentrification often threatens the cultural assets of established neighborhoods, while sprawl exploits nature to create new ones. Mitigating these destructive patterns at both ends will only make us better neighbors, better citizens, and ultimately better people.

Car Troubles

Picture this: it’s nearly eight o’clock in the evening and your wife calls to say she’s having car trouble. The problem is, she’s in Austin and you’re 80 miles down the road in San Antonio. What do you do?

During regular business hours, the protocol is fairly straight forward. Call roadside assistance to have them send a tow truck. Call a rental car company that will pick you up where your car left off. Assuming you have the emergency funds to cover these things, the system works moderately well. But after repair shops and rental companies close for the evening, that’s where things quickly fall apart.

Tow companies start discussing storing your car overnight at some unknown location. The only rental cars available are at the airport, and those guys aren’t coming to get you. Suddenly you’re on the side of the road with almost no options. And, for a woman to take a cab alone at night is not exactly ideal.

Ultimately, I drove from San Antonio to pick up my stranded wife when this happened to her. It took more than two-and-a-half hours to address a problem that ultimately lies with the broader transportation system. We’ve built our environment such that we rely so exclusively on the private automobile, we are quite handicapped when the car quits. In fact, even if distance were not an issue, my wife couldn’t have walked home because our apartment is only accessible from the freeway.

Yet, communities fight against comprehensive transit systems and against organized ridesharing. They fight against development at densities that reduce our total dependency on vehicle ownership. People fail to fight for the utility that a broad car sharing network ultimately brings, even insisting that the driverless car will be the thing that saves us (I hate to burst your bubble, but it won’t).

Often I see arguments against shared transportation shrouded in the term freedom. I’m told time and again that having your own car gives you the freedom to go where you want, when you want. But is spending a third to half of your income on transportation really freedom? Is it really freedom to spend your hard-earned money to insure something that won’t always ensure a reliable means of getting around? Is it really freedom to be tied down to annual inspections, vehicle registrations, standing at gas pumps, sitting in dingy repair shops, or sitting in traffic? Is it really freedom when you’re bound to months of physical therapy after getting rear-ended? Is it really freedom when you lose a loved one to a car wreck?

My wife was not feeling free last night as she waited for a tow truck to pick up our trusty Honda. She didn’t feel free standing in the dark waiting for me to drive in from out of town to give her a ride. And we certainly won’t feel free when the repair shop swipes our card to pay for whatever is wrong with the car.

Sure, my wife and I learned from this experience that it’s important to have a clear contingency plan for situations like this. But, to a greater degree I hope we all learn the value in building lives—and places—that don’t fail us when our vehicles do. Knowing we might one day be able to get around any way we’d like to: now that is freedom.

Excuse me, sir, your bigotry is showing…

Over this past year I’ve grown more concerned with the use of terminology like “preserving neighborhood character” or “quality of life” in neighborhood plans. Sure, they sound well meaning and play to our sense of nostalgia for a bygone era. But, as I’m coming to learn, these vague notions are often held by community members as shields against the types of development they feel threatened by.

Put more bluntly, I worry that we as planners and civic leaders have allowed the use of these ambiguities as convenient covers for bigotry. When neighbors oppose things like granny flats (accessory dwelling units), on-street parking, or apartments, they essentially assert a belief that the “right” to ever-increasing property values for homeowners trumps equitable access to a community. Sure, they may show up to city council meetings and warn us about the impending gridlock a new duplex will cause to their street, but what they’re really against isn’t the traffic, but the people who make up the traffic.

Some neighborhood groups are clever in their approach to NIMBYism. I’ve heard such complaints under the guise of concerns about garbage bins in the street, safety for kids playing outside, and damage to the environment. Others seek to instill fear in their neighbors by insisting that multifamily housing or transit will bring crime.

One Austin neighborhood was a bit less covert: they specifically outlined the sorts of properties believed to be incompatible with the neighborhood. Together on that list were apartments and “AIDS houses.” I’m not sure how the two are comparable, or why so-called AIDS houses were named in the first place, but I’d like to know how this ever flew past an attorney’s radar before being adopted by the local council.

If we hope to ever make progress in overcoming bigotry as a society, or at least working to foster more inclusive neighborhoods, we need to throw out the nebulous language and require citizens to be specific about what is important to them. The built environment is tangible; the guidelines supporting its development should be tangible as well.

If “neighborhood character” means ensuring that homes are no taller than two stories, for whatever reason, then let’s be clear about that. Want more trees to shade the sidewalks or decorative streetlights so you can feel safer walking your dog in the evening? Then say so. But, if your unspoken intent is to keep the very people out of your neighborhood who keep it functioning—emergency response workers, teachers, service-sector employees, garbage collectors, single parents with school-aged children, students, minorities, and anyone else—it’s time we put that language (and that mindset) back into the 1950s where it belongs.

MetroRapid: The Good, The Bad & The Bumpy

Bus Rapid Transit (or BRT for short) has grown in popularity over the last decade, touted by planners as the perfect precursor to rail. It’s relatively cheap, features flexible routes, holds more passengers per vehicle than traditional buses, and welcomes those passengers through any of its doorways, thus speeding boarding times. Capital Metro promised to do the same with its recently-opened MetroRapid, which will include two lines when fully completed this summer. Sadly, early reports have many wondering whether CapMetro is living up to its promises for MetroRapid, especially considering transit advocates have pointed out that MetroRapid doesn’t actually qualify as BRT.

I had my first opportunity to ride MetroRapid a week ago and, at a friend’s request, I’ll share my thoughts on the experience (or you can scroll down for the summary). First, I’ll explain the circumstances that brought me on board:

I took my wife’s car to get the interior cleaned out, and discovered that the detailing place was within walking distance of Route 801’s Koenig station. So, before my trip I downloaded CapMetro’s mobile app and while walking to the bus stop I set up my credit card to buy my first fare—a premium day pass at $3.00. I took the bus downtown, hoping to get in a workout and spend some time at the library during my three-hour wait. As it turned out, the library was closed for Memorial Day weekend, but that’s another matter.

Arriving at Koenig station, I immediately made two observations. For starters, calling it a station is generous. I’ve stood at regular bus stops in other cities that provided more shelter than these. Secondly, the Koenig station location is strangely remote. Just behind the southbound station is a large water reservoir, hidden by a fence. If the goal is to guide development around transit, it’s not gonna happen at this location without major changes. So unless you work for Texas DPS—or happen to need that cat smell blasted out of your car’s interior—the Koenig station doesn’t appear to work well.

Image: Notice the lack of development around Koenig’s southbound station. A large water reservoir is cited just beyond the fence.

One interesting opportunity the trip gave me was to compare the timing of MetroRapid to CapMetro’s local bus, Route 1. The local bus arrived at the adjacent Koenig stop roughly three or four minutes prior to MetroRapid. Yet, it was not until MetroRapid reached downtown that we caught up to the local bus, despite its many more stops along the way.

Now for the experience itself:

Thankfully, boarding MetroRapid itself was uneventful. The QR code scanner worked as designed on each bus I rode, although getting the QR code to appear on the app was not as intuitive as it should be. Once I took my seat, however, I forgot why I paid for a “premium” pass at all. Aside from its accordion-like center, MetroRapid feels like any other bus. At its best it rides like a boat on choppy waters, and at its worst I wonder if my kidneys will survive without permanent damage.

Driving through UT’s campus along Guadalupe felt especially jerky, thanks to all the stops and starts you would expect driving in an urban area. But wait…shouldn’t there have been signal priority? Nowhere along this route did we breeze through signaled intersections, whether near Triangle, UT, or downtown.

What about lane priority? MetroRapid has access to a ‘bus only’ lane downtown—precisely where the road is so wide that cars won’t miss losing the lane. Well, that is, if the cars notice they aren’t allowed in that lane. Construction happened to be going on through a good chunk of this area on Guadalupe anyway, removing the priority lane from use during my inbound trip. In fact, one station was blocked completely, requiring the bus driver to announce that stop was closed. At least that’s what I think he said…the man sounded like he was chewing a whole pack of Bubblicious, so it’s hard to know for sure.

So, here’s the summary:

PROS

- Ability to pay for ticket in advance

- Board bus from any of three doors

- Seats more passengers than a standard bus

- Know when next two buses are arriving

- Stations have button-activated announcement of upcoming buses

- Full-day pass is affordable and works on both MetroRapid and local buses

CONS

- Still feels like a bus

- Bus still waits for passengers paying fare with cash before departing

- Bikes must go on front rack, requiring the bus to wait

- Service is too infrequent

- Still stops at most traffic lights

- Shares a lane with unpredictable traffic for most of route

- Flawed station design: Difficult to read screen when standing at stop; Station area map hidden behind station; Provides little shelter from sun or rain; No recycling bins available (one of the stops had no trash can either)

WAYS TO IMPROVE

- Full lane dedication throughout the corridor

- Ensure signal priority throughout the corridor

- Eliminate on-bus payment to speed boarding

- Increase frequency during peak periods to 10 minutes or less

- Allow bikes on the bus to speed boarding

- Redesign stations with better shelter from weather

- Relocate remote stations (like Koenig) to areas with substantial development and potential for increased density

- Minimize overlap of MetroRapid with local buses to prevent “bus bunching” at shared stops

- Refine app to allow one-tap access to your virtual ticket